Would You Willingly Mummify Yourself — Alive?

Picture this: A monk sits cross-legged in a dim, stone chamber buried deep within a forested mountain in northern Japan. No light. No sound. Just the slow passage of time and the rhythmic ringing of a bell — a signal to the world above that he is still alive. Until one day… the bell stops.

He is not dead in the traditional sense.

He is transcending.

This isn’t a lost tale from some ancient scripture. This is real. It is called self-mummification, or Sokushinbutsu — a practice so extreme and awe-inspiring, it feels like something out of myth. Yet, the evidence still sits — literally — in hidden temples, watching over travelers brave enough to seek them.

This is not just death. It is transformation.

Not just history. It is a spiritual Everest.

And yes — you can go see it with your own eyes.

>> The Yonaguni Underwater Pyramid: Mystery of Japan’s Submerged Monument

The Ritual of Self-Mummification: A Journey Into Nothingness

Self-mummification was practiced almost exclusively by a sect of Japanese Buddhist monks known as the Shingon monks, between the 11th and 19th centuries. These monks didn’t believe death was an end. To them, it was a doorway. And some believed that with intense discipline and spiritual purification, they could cross that doorway — while preserving their bodies to inspire future generations.

Thousand-Day Fasting — Drying the Flesh

The first stage of the process was a 1,000-day extreme fast. The monk would live in isolation, surviving only on natural elements like nuts, seeds, pine bark, wild berries, and roots — all gathered from the forests. No processed food. No grains. No salt. Every bite had one purpose: to eliminate every ounce of fat from the body.

Why? Because fat rots. And rot means failure.

During this time, the monk would continue daily meditations, chants, and laborious physical rituals. They were not preparing to die. They were preparing to be eternal.

Internal Preservation — Poisoning the Body

Once the body was sufficiently emaciated, the monk would drink a special tea made from the sap of the urushi tree — the same toxic sap used to make lacquerware. The tea acted as a natural preservative, but it was also poisonous. It killed off bacteria and parasites — both inside the monk’s gut and on the skin — reducing the chance of decomposition after death.

This was not a quick process. It took months.

Vomiting. Pain. Seclusion.

But they welcomed it — believing this suffering would purify them further.

>> Battleship island: The strange legacy and dark history of Hashima, Japan

Sealed in Stone — Waiting for Immortality

The final stage was the most harrowing. The monk would be placed inside a small stone tomb just big enough for him to sit in the lotus position. A bamboo tube provided air. A tiny bell was held in one hand.

Every day, he rang the bell.

Every day, the other monks listened.

And when the bell stopped ringing… the tomb was sealed.

He was now in a state beyond death, they believed — beyond decay, beyond time.

A full 1,000 days later, the tomb would be reopened. If the monk’s body was perfectly preserved — dry, intact, unrotted — he was declared a Sokushinbutsu, a living Buddha. Not just honored. Worshipped.

If the body had decayed, prayers were still offered, and he was buried with respect — but not enshrined.

Where to See the Self-Mummified Monks Today

Only about 16 known Sokushinbutsu remain today, mostly found in remote temples across Yamagata Prefecture, particularly around the Dewa Sanzan (Three Sacred Mountains) region — a spiritual hotspot in northern Japan.

Here are a few places that every explorer and spiritual adventurer must visit:

Dainichi-Bō Temple – Mount Yudono

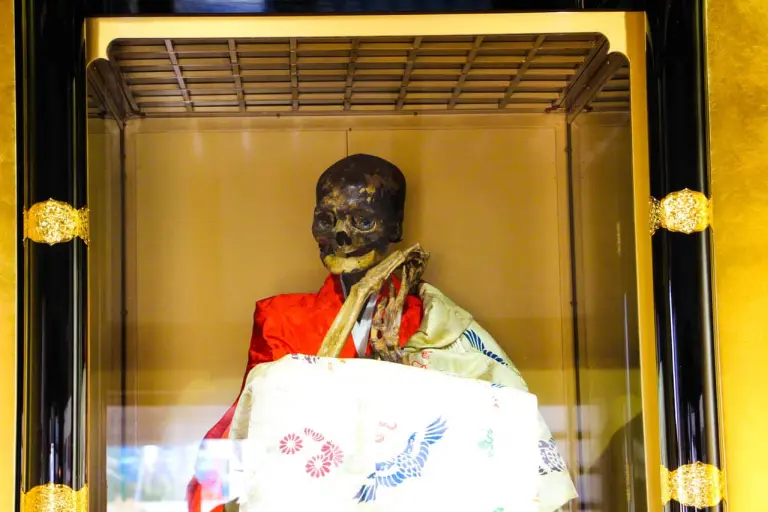

Home to Shinnyokai Shōnin, perhaps the most famous Sokushinbutsu. His preserved body, seated calmly in lotus posture and robed in bright silk, is displayed for visitors. His eyes are closed, lips relaxed — as if mid-meditation. He mummified himself in 1783 after years of devotion.

The journey to Dainichi-Bō is an adventure itself: winding mountain roads, silent forests, and hidden shrines veiled in mist. It’s like entering another world.

Churenji Temple – Near Mount Gassan

Another Sokushinbutsu monk, Tetsumonkai, resides here. His story is laced with mystery — some say he was a former samurai turned ascetic. His preserved body, still intact after nearly 200 years, offers a striking glimpse into the power of faith over flesh.

>> The 3,000-year-old sacred tree at Takeo Shrine, Japan

Why This Journey Will Change You

This is not just dark tourism. It’s not horror. It’s not morbid curiosity.

Visiting the Sokushinbutsu sites is like stepping into the very heartbeat of Japan’s forgotten spiritual past — a side of the country no tourist brochure will tell you about.

You will walk ancient stone paths monks once used for their meditative pilgrimages.

You will smell incense rising in centuries-old temples hidden in cedar forests.

You will see — truly see — what it means to dedicate one’s entire existence to a cause greater than life itself.

And you’ll walk away changed.

Not because you saw something strange.

But because you saw something sacred.

>> Masuda Rock Ship: A Millennia-Old Mystery Hidden in Japan’s Hills

Travel With Purpose, Not Just for Pictures

If you’re the kind of traveler who craves mystery, authenticity, and soul-shaking stories, this pilgrimage is for you.

Don’t just take a photo in front of a shrine.

Sit before the silent remains of a monk who chose to become immortal.

Listen to the wind around Mount Yudono.

Feel the weight of history and the lightness of devotion in the same breath.

Because some journeys aren’t meant to entertain you — they’re meant to awaken you.